LIVING THE PATH TO CHRISTIAN UNITY (Ouellet)

LIVING THE PATH TO CHRISTIAN UNITY

THE POTENTIAL OF MIXED MARRIAGE FAMILIES

FOR PROMOTING CHRISTIAN UNITY

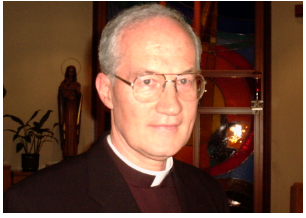

Bishop Marc Ouellet

Bishop Marc Ouellet PSS, Secretary to the Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity, will join the conference for August 3rd and 4th. Bishop Ouellet replaces Cardinal Walter Kasper as Secretary of the Council

Bishop Ouellet was born in 1944 in La Motte, Québec, ordained to the priesthood in 1968 as a member of the Company of Saint Sulpice, served as rector at the Grande Séminaire de Montréal from 1990-1994, and of St. Joseph’s Seminary in Edmonton from 1994-1997. He is Chairman of Dogmatic Theology at the John Paul II Institute of the Pontifical Lateran University of Rome. From 1995 to 2000, Father Ouellet was a consultor for the Vatican Congregation for the Clergy.

In October 1995, Bishop-elect Ouellet acted as a resource person on the spirituality of diocesan priests for the annual plenary meeting of the Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops, held that year in Edmonton, Alberta.

The Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity is entrusted with the promotion within the Catholic Church of an authentic ecumenical spirit and to develop dialogue and collaboration with the other Churches and world communions.

When I was asked to address this audience some days after my episcopal ordination, I did hesitate to accept for I felt unprepared to meet the needs of interchurch families and to appreciate their real and possible contribution to Christian unity. On the one hand I was very interested in your experience, but I felt that I needed more time to develop a deeper sensitivity to your problems and hopes. On the other hand, my experience of teaching young couples for the last five years at the John Paul II Institute for Studies on Marriage and the Family in Rome, represented to some extent an asset for initiating a fruitful dialogue with you. In the meantime, I met Ruth and Martin Reardon whose participation in an ecumenical meeting in Northern Ireland was an impressive testimony and a call to dialogue and further reflection on the potential of mixed marriages for the future of ecumenism. I felt confirmed though at the same time intimidated by their rich experience, to which I cannot offer an adequate counterpart.

The first thought that came to my mind when I began to prepare this conversation was a greeting, a very simple biblical greeting: Shalom! Peace! The greeting of the Risen Lord on Easter Evening when he appeared to the disciples for the first time. Shalom! Receive the Holy Spirit, the Spirit of Easter which is peace, reconciliation, forgiveness and divine communion. Peace to all of you brothers and sisters who are especially bound to Christ and the Church through baptism and marriage. May the grace of the Risen Lord help you to overcome obstacles and to build up the complete and perfect communion that He prayed for!

"Living the path to Christian unity: the path travelled-past and future". I will address this challenging topic mainly by restating as simply as possible the position of the Catholic Church on mixed marriages, with the help of the Directory for the Application of Principles and Norms on Ecumenism. It might prove to be useful for you since you, have been sharing ideas and proposals aimed at promoting unity among the Churches. A sense of momentum is growing among you concerning the contribution you can make to Christian unity. I rejoice about that and I wish to support you as much as I can, by helping you to understand the position of the Catholic Church from the perspective of the family as "domestic church". I propose three brief steps as a starting point for our dialogue: I) The emergence of the family as an ecclesial category in the wake of the Second Vatican Council; II) The impact of the "domestic church" awareness on the Directory for the Application of Principles and Norms on Ecumenism (DE); III) The potential of mixed-marriage families for promoting Christian unity.

I) First, the emergence of the family as an ecclesial category. One of the most prophetic teachings of the Vatican Council II was the emergence of the "domestic church" as a category for affirming the family as the first and primordial "community of love and life" in the Church. The expression "domestic church" is used explicitly only twice in the official documents, but they are very important references, in Number 11 of the Constitution of the Church Lumen Gentium and in the Decree for Lay Apostolate 11. These references are discreet but they have set the tone and opened the path for further development. After the Council and over the past 30 years, no topic has received more attention than the family in the Catholic Church's teaching. Confusion and crisis in our culture have certainly motivated these developments, but there has developed also, a deeper understanding of the family as domestic church, an awareness which has been inspired and strongly promoted by John Paul H's insights on human love in God's design according to biblical Revelation.

In the encyclicals Humanae Vitae (1968) to Evangelium Vitae (1995) and especially the Apostolic Exhortation Familiaris Consortio (1981) and the Letter to Families, (1994) Popes Paul VI and John Paul II have dedicated much attention to the present crisis of marriage and to-day's culture. The thrust of this teaching goes beyond the realm of moral law. It aims at restoring Christian anthropology which has been distorted by modern ideologies such as individualism, communism, materialism and consumerism. People may disagree with some aspects of these teachings, especially if they do not belong to the Catholic Church, but most people will recognize that the category of "domestic church" as developed in these documents, constitutes a very positive development of the spirituality and the mission of the family. Since the first year of his pontificate, John Paul II has constantly emphasized that "the family is the way of the Church". He wrote in his Letter to Families: "We wish both to profess and to proclaim this way which leads to the Kingdom of Heaven (cf. Mt. 7,14) the way of conjugal and family life. It is important that the communion of persons in the family should become a preparation for the communion of saints" (LF 14). As domestic church, the family is a school of communion, based on the values of the Gospel, involving the whole life of the persons in a communion of faith and love which participates in the communion of the divine Persons through the gift of the sacrament of marriage.

This development of magisterial teaching is not something isolated and purely for the confessional Catholic. Already in the thirties, Romano Guardini had coined the concept of an "awakening of the Church in souls". Vatican II was a high point of this awakening, by increasing Church awareness among all the faithful and especially by introducing the concept of the family as "domestic church". This awakening obviously extends beyond the borders of the Catholic Church, since the ecumenical movement, for example, one of the greatest manifestations of this awakening of the Church in souls, was born from Protestant and Orthodox initiatives. As regards further development in the official teaching of the Catholic Church, the conviction now is that the family is not only a focus of the pastoral care of the Church, but also belongs to the very communion and mission of the Church. The family is Church in the first place, as communion of persons united by the bond of human and divine love, sent to the world to bear the fruit of love and life. The Apostolic Exhortation Familiaris Consortio affirms that the family, born of the sacrament of marriage, is not only a community that is "saved" by the love of Christ; she is also a "saving" community by her sharing with others the love of Christ (FC 49). These perspectives reveal the potential of the "domestic church" for an authentic spirituality of marriage and the family; they provide the theological underpinning for allowing families and interchurch families to commit themselves to bring about greater unity among the Churches and ecclesial communities. Your enthusiasm is a concrete sign that the path travelled up to the present, allows us to continue along this way with a deeper consciousness of the gift of God to the family and thus with a greater hope of contributing more to the coming of the Kingdom.

This positive development brings us now to the fundamental question of the unity of the family as domestic church and of the differences among the Churches and ecclesial communities of which mixed marriages form a part. The pressure of contemporary culture which challenges family values, makes man realize that only a deeper encounter with Christ can enable the "domestic church" to bring about unity among the Churches. I remember fondly the gift I received from my students last June at the end of my course on the sacrament of marriage: it was a reproduction of a mosaic from the famous Basilica of Montreale in Sicily showing Christ bringing Eve to Adam in the garden of Paradise. Christ occupies the centre of the picture; He holds Eve firmly by the hand in front of Adam who is seated with his finger pointing towards her, as he exclaims, marvelling: "Yes, this is the bone of my bone and the flesh of my flesh!" What is striking in the picture is Christ at the centre appearing as Creator and Lord of human Love. The message of this picture is important for Christian couples and for interchurch families because it reveals Christ as the best friend of human love and as the key to the unity of the family and the unity of the Church which are two inseparable realities. Christ is the One who ultimately shapes and blesses the relating of man and woman for the sake of the Kingdom. It is this centrality of Christ in sacramental marriage, brought to the fore by the Vatican Council, that allowed the family to emerge as an ecclesial category. My students knew that this picture encapsulated a great part of my teaching and they were grateful to me for having introduced them into the nuptial mystery of Christ and the Church which is so central to marriage and family.

When a man and a woman come together before God and the minister of the Church to exchange their vows, they commit themselves for life, relying not on their human strength but on the grace of God which is given to them in the sacrament. In fact, the celebration of the sacrament is an act of faith by which the two baptised partners give their vows to Christ in the hope of being blessed by Him. The Lord welcomes them and blesses them with the Gift of Love that binds him to the Father: the Bond of the Spirit. Christ brings Eve to Adam. Christ brings Erika to Andrew, He gives Peter to Karina and binds them forever with a divine bond of Love; the Holy Spirit poured out upon them through the sacrament of marriage. Such a gift means concretely that human love and family life are blessed by the grace of strengthening, healing, and nurturing their communion all the days of their lives. The family is domestic church precisely because of the presence of the Lord in the communion of the spouses. This presence is a precious gift which belongs to the baptised couple as their ecclesial bond, when it is properly received according to the canonical form of the Church. This bond is more secure when the couple belong to the same faith and Church, which is the ideal, but it is there too for a mixed marriage of two baptised people belonging to different Churches or ecclesial communities. This gift promotes unity and fruitfulness in the couple and flourishes naturally through welcoming the children or through any spiritual fruitfulness that God wants to give to the family. This blessed bond constitutes the deepest identity of the married couple, its ecclesial identity; it provides them with a source of holiness and mission which involves the married couple in the mission of Christ and the Church.

Here I move to the second point of my presentation: II) The impact of this "domestic church" awareness on the Directory for the Application of Principles and Norms of Ecumenism (DE). In Chapter Three on Ecumenical Formation in the Catholic Church, among the suitable settings for formation, the family is given the first place: " The family, entitled the "domestic church" by the Second Vatican Council, is the primary place in which unity will be fashioned or weakened each day through the encounter of persons, who, though different in many ways, accept each other in a communion of love" (DE 66a). Mixed marriage families share in that primacy in spite of the differences in faith and Church membership. Thus, it entails for the parents, the primordial duty proclaiming Christ, by word and example, to their children. Moreover, the document continues, in bearing witness to Christ, "they have too the delicate task of making themselves builders of unity" (DE 66b)1. The rationale for this delicate task is explained in these terms: "Their common baptism and the dynamism of grace provide the spouses in these marriages with the basis and motivation for expressing their unity in the sphere of moral and spiritual values" (DE 66b).

It is worth noting here the great difference between this formulation of the DE, which quotes the new Code of Canon Law and the expression of the old code. In 1917, the Catholic Church's Code of Canon Law proscribed mixed marriages: "The Church everywhere prohibits the marriage between two baptized persons, one of whom is a Catholic, the other of whom belongs to a heretical or schismatic sect" (c. 1060). At that time, a mixed marriage was generally considered as something evil and to be avoided. In 1983, however, the Code was specifically revised in the matter of "mixed marriages". It now reads: "Without the express permission of the competent authority, marriage is prohibited between two baptized persons, one of whom was baptized in the Catholic Church. . . the other of whom belongs to a Church or ecclesial communion not in full communion with the Catholic Church" (c.1124). There is an important softening of both language and attitude between these two formulations. It speaks of other communions not in full communion with the Catholic Church but not any more of a schismatic sect. In keeping with the revised Code, the DE underlines the positive values of mixed marriages and their delicate task of being builders of unity. Man realizes how the ecumenical spirit has already accomplished much, not only in terms of language but also in terms of building a real, albeit incomplete, communion between the Churches and ecclesial communities. This is reflected also in changes of the Catholic Church's regulations concerning the education of children and sacramental sharing.

In keeping with her doctrine on religious freedom, the Catholic Church has modified the requirement of a promise by both partners to educate their children in the Catholic faith. While it was previously an indispensable condition for giving permission for a mixed marriage, the terminology is now considerably transformed: "In carrying out this duty of transmitting the Catholic faith to the children, the Catholic parent will do so with respect for the religious freedom and conscience of the other parent and with due regard for the unity and permanence of the marriage and for the maintenance of the communion of the family. If, notwithstanding the Catholic's best efforts, the children are not baptized and brought up in the Catholic Church, the Catholic parent does not fall subject to the censure of Canon Law" (CIC 1366). In other words, the parents are not punished if, out of respect for the other, they fail to realize fully their educational duty. This change of regulation does not mean that the obligation of Catholic education of the children ceases: it does remain and must be fulfilled in different ways. But it is important to note that an important ecumenical step was made by the fact that "no formal written or oral promise is required of this partner (non-Catholic) in Canon Law" (DE 150).

The most delicate question is obviously sacramental sharing and especially Eucharistic sharing. For many interchurch couples it is the neuralgic pastoral question. The norm of the Catholic Church is often challenged or considered inadequate to the needs of interchurch families. Several factors make it difficult for them to be restricted in this area, for example the pressure of the other partner, the different policy of other Churches (except the Orthodox Church), the felt need of spiritual nourishment and the confusing and divergent interpretations of the Catholic norm. The norm reads like this: "Although the spouses in a mixed marriage share the sacraments of baptism and marriage, Eucharistic sharing can only be exceptional and in each case the norms concerning the admission of a non-Catholic Christian to Eucharistic communion, as well as those concerning the participation of a Catholic in Eucharistic communion in another Church, must be observed" (DE 160). Canon 844,4 spells out the conditions of this exceptional permission: " If there is a danger of death or if, in the judgement of the diocesan bishop or of the episcopal conference, there is some other grave and pressing need, Catholic ministers may lawfully administer those same sacraments (Penance, Eucharist and Anointing of the Sick) to other Christians not in full communion with the Catholic Church, who cannot approach a minister of their own community and who spontaneously ask for them, provided that they demonstrate the Catholic faith in respect to these sacraments and are properly disposed".

I will not plead here for a change of the norm, though the norm is provisory and could be changed in the future according to the development of communion among the Churches and ecclesial communities. Since the DE is fairly recent and its possibilities of adaptation have not yet been fully explored and put into practice, I will focus on some aspects of the regulations which are open to a non-restrictive interpretation. First of all, it is worth remembering that the Vatican Council in its document on Ecumenism affirms two main principles upon which the practice of common worship depends: "First, that of the unity of the Church which ought to be expressed; and second, that of sharing in the means of grace. The expression of unity very generally forbids common worship. Grace to be obtained sometimes commends it" (UR 8). In the light of these principles, Eucharistic sharing, according to the prudent pastoral judgement of the competent authority, may be commended. Therefore, Eucharistic sharing is not just a concession which is tolerated, it is a mean of grace which is commended in exceptional circumstances, in spite of the division of the Churches. Hence, the normative statements of the Code and of the DE have to be interpreted in the same spirit as the Conciliar document; it ought not to be interpreted restrictively as if Communion for mixed marriages was a mere concession to be restricted to the minimum.

As stated above, the DE indicates that in cases of pressing need, to be determined by episcopal conferences or local bishops, eucharistic sharing for mixed marriages may be permitted, provided that the general conditions for Eucharistic communion are respected. Some episcopal conferences have issued more precise guidelines in that regard, for example, the Bishops of Great Britain and Ireland in 1998, establishing that on special occasions, such as baptism, confirmation, first communion, ordination and death, Eucharistic communion would be commended.

Pastorally the establishment of objective criteria for "serious (spiritual) need" is extremely difficult. Does the couple concerned (and any children) experience this separation at the Lord's table, as a pressure on their life together? Is it a hindrance to their shared belief? How does it affect them? Does it risk damaging the integrity of their communion in married life and faith?. These questions require the careful attention of the ministers and should be addressed in pastoral dialogue with the mixed marriage couples. Pressing need may vary from case to case; without allowing a general practice of Eucharistic communion, it should be considered in keeping with the two basic principles: commended in particular situations of pressing need as a mean of grace, but restricted to exceptional cases because of the incomplete communion of the Churches.

Even if the norm is more open than some interpreters may think, it remains important to accept it and to apply it adequately so that interchurch families may accordingly make their contribution to Christian unity. The Bishops of Great Britain and Ireland speak in this regard of the pain of division which is deeply felt by these families but according to them, the pain of the broken body of Christ cannot be healed simply by removing the pain of not sharingcommunion (palliative care). Healing is achieved only by dealing with the underlying problems between the Churches. The differences at that level are real and do not allow full Eucharistic communion on a general basis, even for the interchurch marriages. The interpretation of the pressing spiritual desire for sacramental communion must therefore not lose sight of the broader sense of communion which involves the domestic church within the broader communion of the Church.

To be in communion with the Catholic Church means not only to receive graces from the sacramental Body of Christ. It means also to follow Christ and to be responsible for the sacramental unity of the One Church. By receiving or abstaining from Eucharistic communion, according to personal conscience and to the discipline of the Church, a Catholic Christian manifests his sense of belonging to the Church. The question of sharing communion or abstaining therefrom, can be viewed, in this perspective, as a spiritual way of bearing the pain of incomplete communion. This pain is felt not only by those who abstain but equally by those who receive. The pain is an integral part of the healing process of reconciliation, which requires time, patience, forgiveness, humility, self-sacrifice and acceptance of the limitations of the partners. Conjugal life invites the partners from time to time to abstain from intercourse for spiritual, moral or health reasons; analogically, the sacrifice of sacramental communion may sometimes mean, paradoxically, a deeper spiritual communion with Christ and the Church. This happens when it is accepted without resentment, in a spirit of respect, obedience, patience and in union with Christ who reconciled humanity with God on the Cross in utter abandonment and desolation. To mixed marriages belongs the difficult and delicate task of building unity through receiving occasionally sacramental grace together and being willing to make this sacramental sacrifice for the sake of ecclesial communion. They do not receive less because they abstain from sacramental Communion. When this is done out of love and respect for the Church, they may even receive more by abstaining than by communicating. This sense of spiritual solidarity is crucial today. It entails an understanding of Christian love which goes beyond the "psychological or social need" of not being left out. It requires special care and explicit support of the pastors who are responsible for helping interchurch families to deal in truth and love, with their unity in diversity.

III) This understanding of the Catholic Church's norm brings now to the last point which I call the ecumenical potential of mixed marriage families. After about a century of existence, the ecumenical movement needs to bring awareness of the achievements of theological dialogue into the broader reception of the Churches. This process of reception requires at the grass roots level more information, more mutual knowledge of the partners and more progressive commitment of authorities and faithful altogether. Mixed marriages are a natural setting for that reception, since they are actually multiplying in our globalizing world and their values are being progressively recognized as special contribution to Christian unity. Though they are not the ideal domestic Church, they offer opportunities to build up very concrete links and bridges between the ecclesial communities to which they belong. Their effectiveness obviously derives from their profound attachment to the Church and from their taking the means to remain in touch with their roots. Unfortunately, it too often happens that the ecclesial link fades away and mixed marriages end up in distancing themselves from the Church. This is a special challenge for pastors but when the challenge is assumed positively, by pastors and faithful, much can be achieved in terms of uniting different ecclesial communions in and through the unity of the family.

According to the Council and to the DE, ecumenical spirituality requires that "in the interest of greater understanding and unity, both parties should learn more about their partner's religious convictions and the teaching and religious practices of the Church or ecclesial Community to which he or she belongs" (DE 149). Mutual knowledge and mutual acceptance of the differences are as important as striving for complete sacramental communion. Mutual knowledge and mutual love grow together and create the conditions for living the path to Christian unity with tolerance, respect and deeper esteem and understanding of the other's values and traditions. This mutual understanding takes time and energy. It does not fall into the impatience of youth which is often tempted to rush ahead with the sexual expression of love without ensuring that the process of human and spiritual maturity of the partners has taken place. We know, for example, the negative consequences of premature sexual intercourse when the conditions of mutual knowledge and commitment are absent. Instead of unity, this fosters instability, infidelity and insecurity in the relationship. Analogically, the still young ecumenical movement may be tempted to push towards universal Eucharistic hospitality, without solving the real problems that are impeding full communion. Therefore, the DE reminds us of the other means of spiritual growth for interchurch families: "They should remember that prayer together is essential for their spiritual harmony and that reading and study of the Sacred Scriptures are especially important" (DE 149).

Conclusion. The universal and the domestic church are so intimately interwoven that they share and suffer together and inseparably the pains and the joys of building unity. Pope John Paul II, Pope of the family, continuing the teaching of the Second Vatican Council, has re-affirmed the commitment of the Catholic Church to work for this unity. At the same time, he has warned us that "to uphold a vision of unity which takes account of all the demands of revealed truth does not mean to put a brake on the ecumenical movement. On the contrary, it means preventing it from settling for apparent solutions which would lead to no firm and solid results. The obligation to respect the truth is absolute. Is not this the law of the Gospel?" (Ut unum sint 79).

The complex and rich experience of mixed marriage families is a challenge and an assurance of renewal for the Church and for the ecumenical movement. I believe that an ecumenical momentum may emerge from the reflection and the discernment in which we are now engaged. What is experienced at the grass roots level and what is discussed in theological dialogue must meet and serve the broader understanding of fuller communion among Churches and ecclesial communities. This urgent but grace-filled objective signals the pressing need of strengthening the ties between pastors and faithful. Only together, in deep communion of domestic and world church, may we hope to better answer the prayer of the Lord for a unity of the Church that mirrors the unity of the Trinity: "May they all be one. Father, may they be one in us, as you are in me and I am in you so that the world may believe it was you who sent me" (Jn. 17, 21).

A reference is added to Paul VI's Apostolic Exhortation Evangehi Nuntiandi 1975, 71.

+ Marc Ouellet

Secretary of the Pontifical Council for promoting Christian Unity

Edmonton, August 4th 2001